This wee gem shows Archie Cochrane, the father of evidence-based medicine, in his prime.

He is the narrator so you see him from the start in a 1970s-style pullover. Then it cuts to scenes from the 1950s – some of which are redolent of the later Cholmondley Warner pastiches.

Update (January 2023) The YouTube link above still works. It shows a short section from a 32-minute film National Screen and Sound Archive of Wales collection which is now available to view on the BFI website: https://player.bfi.org.uk/free/film/watch-research-in-the-rhondda-a-film-of-a-medical-survey-in-south-wales-in-1968-1969

Archie is best known for the collaboration that bears its name – an international movement which scrutinises evidence from medical trials to find out what actually works for patients and what doesn’t.

But this is his great project in the Welsh valleys which resulted in the Rhondda Fach becoming the most medically-examined community in the world.

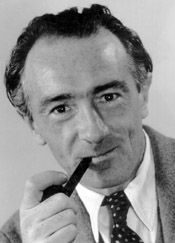

Archie with pipe – he smoked cigarettes too as did most doctors of that era. Courtesy of Cardiff University

At first sight, he seems a bit out of place – posh Scottish doctor with a plummy accent, a Cambridge double first and his own private income (enough for him to afford a top- of- the- range Jaguar).

It makes you ask questions, which is what Archie did all the time. Sometimes awkward questions which rankled vested interests and rumbled conventional orthodoxy.

It may be a Scottish trait of constantly inquiring cussedness but that‘s the way he was. And for those who loved his integrity, loyalty and friendship it was a minor foible. Archie also had the Scotsman’s ability to dispense a ready dram and start a party anywhere.

After school and university he studied in Berlin and Vienna where he became fluent in German. He then enrolled as a medical student but with the advent of the Spanish Civil War he joined the International Brigade.

On leave in bar in Madrid he encountered Ernest Hemingway (“an alcoholic bore”). In a Barcelona bar he had a long argument with a tall Englishman over the POUM militia’s failure in the Aragon offensive to take Huesca and Zaragoza. That was Eric Blair aka George Orwell.

As a medical orderly, Archie also suffered every triage nurse or doctor’s nightmare – admitting a wounded Julian Bell, a close pal from their Cambridge days, knowing that he was certainly going to die.

Spain confirmed his affinity with ordinary working people and his hatred of fascism. That was further seared during his war service. Like his friends Richard Doll and John Crofton, his war was traumatic – all the more so as a prisoner of war when he had additional pressure as a doctor who could speak German.

In such adverse conditions he managed to conduct some trials and also help some Spanish volunteers in Salonica who faced a tough time explaining why they were fighting with the allies. Archie told the German authorities they had all been born in Gibraltar and were therefore British.

Archie studied under Austin Bradford Hill, the leading medical statistician who provided the randomisation model for trials. Later, he almost carved a career in his native Scotland but a Scottish Office and Medical Research Council (MRC) project fell through. So he came to Wales joining the MRC’s Pneumoconiosis Unit at Llandough Hospital, Cardiff.

This was at the start of the National Health Service which already had strong associations with South Wales and mineworkers. Its founder Aneurin Bevan (whose father died from pneumoconiosis) was from Tredegar which had long had its own comprehensive health service paid for by miners and steelworkers.

The Scottish doctor AJ Cronin worked for the Tredegar Medical Aid Society and every week would roar up the valleys on his motorbike to pursue his studies in Cardiff. His experiences with the mining community formed the basis of The Citadel the novel turned into Hollywood blockbuster which hardened British public opinion in favour of a national health service. (I looked very hard for evidence that he and Bevan actually met in Tredegar but, dammit, could not find any!).

But for Archie it was a relatively favourable environment. The wee Jock with the big Jag had fought fascists and Nazis so his credentials were OK. Around one in twenty miners suffered some sort of disability from working in the pits. It was these men he recruited for the study. They were the key to its success, ensuring an astonishing response – more than 90 per cent of the population agreed to take part.

Its main aim was to see if the common miners’ disease progressive massive fibrosis (PMF) was due to an interaction between pneumoconiosis and tuberculosis. In the end, it concluded that tuberculosis had relatively little or no impact.

Archie followed the research up over 20 years. Its real impact was to demonstrate that epidemiology – looking at the pattern of disease – could be carried out effectively in large-scale field studies as well as the laboratory. If Tredegar was the cradle of the NHS, the Rhondda Fach was its nursery. South Wales also broke new ground in historiography with the Craig-y-nos project recreating the story of a TB hospital through the memories of former child patients.

In the 1960’s Archie expanded his questioning to other areas – use of aspirin to prevent heart attacks and the relative value of specialist coronary care units. In 1967 he asked what the evidence was for cervical screening programmes and concluded it was very flimsy. This was picked up by a newspaper reporter and was the first, but not the last taste, of media controversy.

The uncomfortable truth which he highlighted in his 1971 Rock Carling lecture Effectiveness and Efficiency: Random reflections on health services was there was no good evidence for many medical interventions and treatments. Too often it was based on subjective ignorance (from fellow doctors, which didn’t endear Archie to many colleagues) rather than objective evidence from randomised controlled trials.

Only after Franco died did Archie return to Spain to revisit his old haunts from the civil war. Overseas travel was not his forte. “…More things happened to Prof. Cochrane when he was abroad than to anybody else since. He got his passport stolen, he was accosted in lifts, he lost his luggage every single time he went abroad” colleague Janie Hughes recalled in a Wellcome witness seminar.

He also directed attention to his personal life and discovered his sexual impotence was due to the inherited disease, porphyria. He then tracked more than 100 members of his wider family to have them tested.

A keen art collector, Archie even ensured questions continued to be asked after his death in 1988. He left a bequest of more than £300,000 to Green College, Oxford, newly established by Richard Doll, with the stipulation that part of the money should be used in the field of randomised trials.

He did not set up the Cochrane Collaboration. This was the work of Iain Chalmers and others first in Oxford and now around the world but he wholeheartedly approved of its aims.

The Collaboration logo (left) shows seven controlled trials of the use of corticosteroids to women expected to give birth prematurely. The first trial was in 1972 and the last in 1991. Lines on the left show positive results for the treatment – cutting the odds of baby death between 30 and 50 per cent.

The Collaboration logo (left) shows seven controlled trials of the use of corticosteroids to women expected to give birth prematurely. The first trial was in 1972 and the last in 1991. Lines on the left show positive results for the treatment – cutting the odds of baby death between 30 and 50 per cent.

The trouble was for two decades doctors simply didn’t know the life-saving benefits of this treatment. It wasn’t until 1989 that the results were brought together in a systematic review. As a result, tens of thousands of premature babies probably suffered or even died.

The explosion in the number of controlled trials has continued unabated since then and with it the work of thousands of Cochrane researchers critically assessing all available trial results and then publishing them.

So Archie’s questioning continues…..

Sources

The Cochrane Archive at Cardiff University is a very good resource and has a paperback edition of Archie’s autobiography One Man’s Medicine. It also houses a collection on Austin Bradford Hill.

Isabel Baker’s informative post on the MRC Insight blog adds interesting details on Archie’s team

The James Lind library (named after the Scottish physician who first conducted medical trials in the 18th century) has very useful Cochrane links.

A wealth of personal and professional recollections of Archie in Wales has been captured in this splendid Wellcome Witness Seminar

Effectiveness and Efficiency: Random reflections on health service – online version from the Nuffield Trust which also has a series of essays on Archie Non-random Reflections on Health Services Research viewable here.

Archie Cochrane: Back to the Front by F Xavier Bosch, Barcelona, 2003 is a very good collection of essays on Archie with particular reference to his time in Spain.

There is a fine Tara Lamont review of Archie’s biography , posted on the BMJ group blog here.

The Cochrane Collaboration has been a leader in harnessing the internet to make its work readily accessible online. This is a good short video of its early years:

Categories: history on the web, gems from the archive, medical and nursing, digital history

congratulations for your work. xavier bosch