As the Second World War was reaching is destructive climax, the holy grail of medical research was finally found – in Gothenburg. Tuberculosis (TB) had wreaked havoc on humankind for millennia. Huge efforts were made to find a cure after Robert Koch first identified the bacterium in 1882. But none came.

It could attack every organ in the body, but most commonly through the lungs, where the wretched victims often drowned in their own blood.

More than half of adults would die within five years of diagnosis. Treatment in sanatoria helped some patients recover but there was no cure.

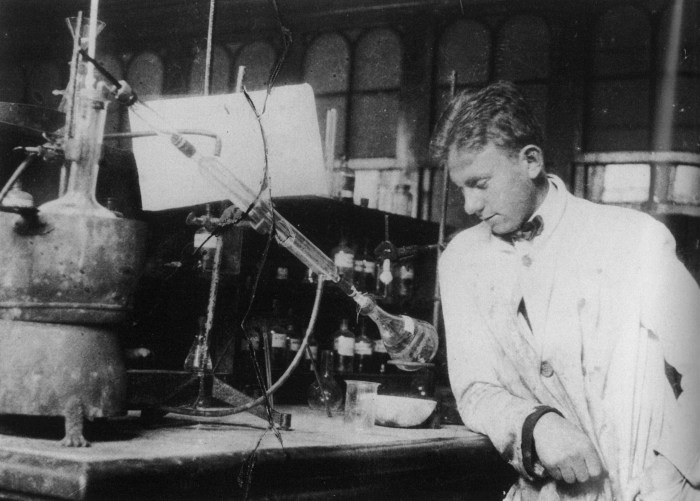

Then came Jörgen Lehmann.

His genius was to see what others hadn’t: the potential to modify the molecule of everyday aspirin into a drug that stopped TB germs in their tracks – PAS (para-amino salicylic acid).

Born in Copenhagen, he qualified as a doctor in Lund and spent time in New York on a Rockefeller scholarship. In 1938 he became head of the new department of chemical pathology at Sahlgrenska hospital in Gothenburg.

Sigrid, aged twenty-four, seemed fine when she gave birth to her first child in February 1944. Within weeks, however, she became dangerously ill with pulmonary TB and was admitted to Renströmska sanatorium.

It then spread to both lungs. PAS was her last hope, and she was given the drug on October 30.

It didn’t get much attention then because the war was still raging. And outside Sweden, it is still largely unrecognised now.

Across the Atlantic, Patricia, aged twenty-two, a farmer’s daughter from Austin, Texas, was in a similarly desperate condition. She had the first injection of streptomycin on November 20 at the Mayo Clinic in Minnesota.

No-one knew the correct dosage for either drug. Recovery was slow and precarious but both women were cured and managed to return to normal life.

After decades of fruitless efforts to find a cure for the disease two had arrived within the space of month. And the world’s media had their first “miracle” drugs to beat TB.

It was streptomycin that grabbed international attention. It had arrived via a different route at Rutgers University in New Jersey where Selman Waksman was exploring soil samples for potential drugs to be developed with the pharmaceutical giant Merck. A PhD student, Albert Schatz, discovered streptomycin.

In contrast, PAS was manufactured by Ferrosan, a small drug company in Malmo. Lehmann had provided the pattern and Ferrosan’s gifted head chemist, Karl-Gustav Rosdahl, turned it into reality.

PAS wasn’t their first collaboration on an important discovery. Lehmann used the same concept of competitive inhibition to produce the clot-busting drug, dicoumarol, the forerunner of warfarin. Coincidentally, another team led by Karl Link ar the University of Wisconsin had made the same discovery.

Lehmann became utterly engrossed in his work and this contributed to the breakdown of his marriage. Contact with the outside world was problematic. Sweden’s neutrality did not prevent attacks on aircraft and ships carrying mail.

The British consul in Gothenburg helped secure a submission from Lehmann to reach the Lancet. His isolation was broken by intermittent letters from his American friends, Frederick Bernheim and Karl Link.

Lehmann was charming and eccentric. Eyes turned during the dicoumarol research when a big truck carrying sweet clover hay arrived at the laboratory with Lehmann pedalling behind on his bicycle.

He sometimes lapsed into speaking Kattegatska, his blend of Danish and Swedish, and he could often be seen riding his black Danish bicycle along the long corridors of Sahlgrenska hospital.

Stung by the disbelief with which Swedish TB physicians initially greeted PAS, Lehmann held off publishing his findings until January 1946.

PAS pipped streptomycin for the first patient to be treated but only by a matter of weeks.

Bizarrely, however, the Karolinska Institute awarded the 1952 Nobel prize for medicine to Selman Waksman alone, ignoring both Lehmann and Schatz (both of whom were also nominated).

There was a recent precedent – the 1945 prize was shared by three scientists Fleming, Florey and Chain for their work on penicillin.

One of the judging panel in Stockholm was rumoured to be jealous of Lehmann’s success and bore a grudge against him.

What mattered most to patients was the cure. Both PAS and streptomycin had treatment failures.

A British Medical Research Council trial showed they worked best when used together from the outset. John Crofton, a junior doctor on that trial, took this further in Edinburgh when a third drug, isoniazid, became available.

The Edinburgh method became the gold standard cure for TB and established the principle of combination chemotherapy now used to treat cancer and other diseases.

Although hurt by the Nobel decision, Lehmann carried on regardless and was feted with other honours.

His reward was saving thousands of lives worldwide and seeing Gothenburg patients being the first to receive PAS for TB, and dicoumarol for heart attacks and embolisms.

Lehmann remarried and continued his research well beyond retirement age into other areas which stimulated his intellectual curiosity. Asked by a colleague why he still worked on in Sahlgrenska hospital, Lehmann replied: “The air in these corridors is life to me!”

Sheffield-based historian and doctor, Frank Ryan, a leading authority on the history of tuberculosis, compared his deductive genius to that of Sherlock Holmes:

“No medical scientist of the twentieth century was ever more unorthodox, more impulsively creative, than this charming Scandinavian doctor, Jörgen Lehmann.”

Read more

My Herald piece on the history of TB and how women were objectified, ignored and largely forgotten: https://www.heraldscotland.com/news/24628735.two-womens-role-curing-tb-gone-unknown/

There is a very good piece here by Anders Lehmann on his grandfather: https://akademiliv.se/2015/01/23289/index.html

And Britain’s awful legacy of dealing with bovine TB. My piece for Health and Care Scotland: https://healthandcare.scot/stories/3966/bovine-tb-history-stiles-mile This is my first picture byline as a cow – some say it’s an improvement.

Frank Ryan’s book, Tuberculosis, the Greatest Story Never Told, remains a brilliant read and is available in print and kindle: https://www.amazon.co.uk/Tuberculosis-Greatest-Search-Global-Threat/dp/1874082006

Categories: case studies, history on the web, medical and nursing

Leave a comment