Think twice about throwing out that old book – the one you picked up yonks ago in a library sale. It can have its uses….in this case shedding light on the leader of the first Luftwaffe raid over Britain.

The attack on October 16, 1939 by Junkers 88 dive bombers on Royal Navy ships in Rosyth was led by Hauptmann Helmut Pohle. After dropping his bombs on HMS Southampton, he was pursued by Spitfires from 602 (City of Glasgow) auxiliary squadron from Drem and he ditched into the sea off Crail.

Pohle, the only member of his crew to survive, was picked up and captured. He suffered a broken jaw and lay unconscious for five days.

Another Junkers was shot down off Gullane by Spitfires of 603 (City of Edinburgh) auxiliary squadron based at Turnhouse. Three survived including Hans Storp, who was the one paraded in front of newsreel cameras. These were the first German prisoners of war.

That’s where it ended for me until I found an old copy in the bookshelf of The One Who Got Away, the story of Swiss-born Franz von Werra, another Luftwaffe pilot, and the only German air force officer to escape and find his way back to Germany.

According to the book, Pohle was a personal friend of Herman Göring and demanded that his captors telephone Berlin to send a Red Cross plane to pick him up. Instead, he was despatched to the Tower of London which was then an interrogation centre.

Pohle was sent to the German officers’ camp at Grizedale Hall in the Lake District where he was one of three senior officers on the escape committee.

Werra arrived in September 1940. Within days he had come up with a plan which got the backing of Pohle and the committee. Pohle led the regular escorted exercise party away from the camp. Near the village of Satterthwaite, Werra legged it over a wall while his comrades sang marching songs as a diversion.

Back at Grizedale, Pohle was hauled off to the commandant’s office whilst the other prisoners celebrated the escape. A hue and cry was launched, details were broadcast on the BBC and Werra was recaptured after five days.

Ever resourceful, he made more attempts until finally jumping from a train in Canada. Werra reached Berlin via the USA, Mexico, and Rome, in April 1941.

At the same time, a number of British prisoners of war were also planning their escape including Lieutenant Chandos Blair. He was among the 51st Highland Division forced to surrender at St Valery protecting the Dunkirk evacuation.

Like Werra, he was obsessed with fitness and a determination to escape. The opportunity came at the Biberbach camp in southern Germany and he made through to Switzerland, finally reaching neutral Spain in January 1942.

Blair is described as the first British army officer taken prisoner to make it back home. His obituaries noted that he eschewed personal publicity and despised those who sought it.

However, in an interview with historian Peter Liddle in 2007 he refers to Peter Douglas as the first British officer to escape from a German prison camp, hidden in a rubbish bin and making it to Sweden via Danzig. Blair also had much help from Canadian wing commander Peter Gilchrist in getting out of Switzerland.

Some sources say he was awarded the Military Cross for his escape. This appears incorrect – the citation (for gallantry) was published in September 1941 when he was still a prisoner in Germany.

Blair had shown great promise as an officer cadet, winning the sword of honour at Sandhurst in 1939 The medal was for courage demonstrated at St Valery. He received a second Military Cross for similar valour in action after the Normandy invasion in 1944.

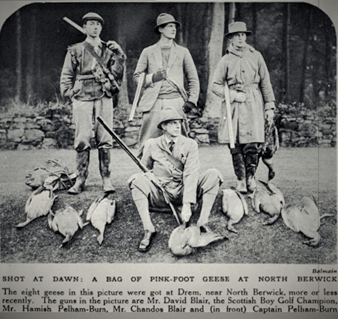

There is a remarkable photograph from the Tatler in 1936 showing Blair with his brother David and Hamish Pelham-Burn after hunting geese at Drem. All three had been boyhood chums in Nairn and later joined the Seaforth Highlanders

In 1942, David Blair, by then in 11 Commando, was captured in Libya He and five others tunneled their way out and made it to British lines in October 1943. He too was awarded the Military Cross in Normandy.

Hamish Pelham-Burn, the man in the middle, was no conventional soldier He trained as a pilot with RAF and later an explosives expert with the Special Operations Executive. He was parachuted into Britanny to blow up radar installations shortly before the Normandy invasion.

In his retirement (and by this time General Sir Chandos) Blair came to Gullane where he was a genial and well-liked figure. His home offered views over the Forth and the ditching points of the first Luftwaffe pilots. Unbeknown to everyone, a section of the starboard wing of Storp’s Junkers had been hastily buried in the dunes at Gullane beach. It was finally recovered and put on public display in 1999.

Werra, in contrast was a flamboyant playboy, a charming chancer who revelled in self publicity. He was a particularly good fighter pilot but was prone to exaggeration.

Born in Leuk in the Valais canton, he might have joined the Swiss air force. It took on the Luftwaffe in June 1940 in dogfights over Swiss airspace. Both had the same Messerschmitt fighters but the Lufwaffe lost 11 aircraft with the loss of just three on the Swiss side.

Werra enjoyed his celebrity status on his return to Berlin in 1941. He was feted at various events. Expressly forbidden from giving press interviews, he was sent on a tour of German prison camps meeting RAF officers.

The Luftwaffe remodelled its own interrogation procedures based on Werra’s experience of the British system.

A journalist prepared a draft of his memoirs, but these were judged to be far too kind to his British captors to be published.

After the war, Hans Storp kept in touch with the family of John Dickson, the fisherman who rescued him. Helmut Pohle was visited in Edinburgh Castle by George Pinkerton from 602 Squadron who brought a box of toffees for the broken jaw. Both farmers in peace time, they later reminisced of their wartime comradeship.

The early chivalry and mutual respect between aviators were shattered in July 1944 with the murder on Hitler’s order of 50 allied air force officers who had broken out of Stalag Luft III. After trial at Nuremberg for war crimes, 13 of those responsible were hanged in 1948.

Death was never far away from air crews. Lieutenant John Webster who had shot Werra down in 1940 was himself killed later that day. Shortly after his marriage and honeymoon Werra took off in October 1941 across the sea. No trace of his nor his new Messerschmidt 109 was found.

Sources:

The One That Got Away by Kendal Bart and James Leasor, London, 1956.

Captured Memories 1930- 1945: Across the Threshold of War by Peter Liddle (Pen and Sword Military, 2011)

Second Supplement to the London Gazette, September 26, 1941

Categories: history on the web

Leave a comment