Even editors of the British Medical Journal can drop a clanger.

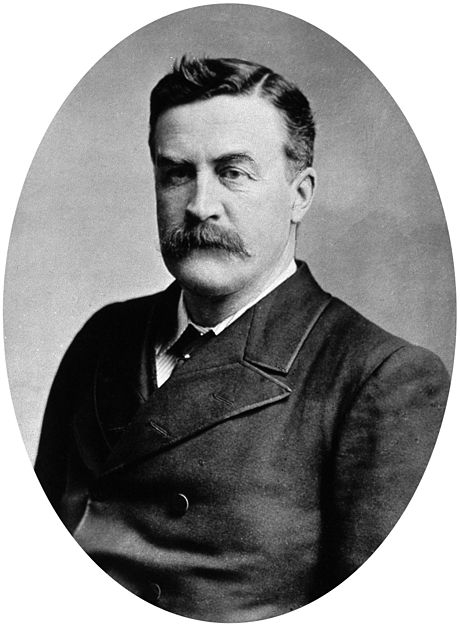

Ernest Hart ranks among the most successful in the journal’s history. Over his 32 years in charge, BMA membership increased tenfold as he transformed the BMJ from relative obscurity into a reputable and highly influential voice for the medical profession.

Not for Hart a couple of paragraphs as an obituary – he got 11 pages in the BMJ when he died in 1898 His writing was fearless and his campaigning relentless. Few of the multiple ills and evils of Victorian Britain escaped an Ernest Hart attack.

Hart was born and raised in London. He qualified as doctor at St George’s and was later dean of St Mary’s Hospital before deciding on journalism. He cut his teeth on the Lancet and departed after a quarrel with its editor. He was appointed BMJ editor in 1866.

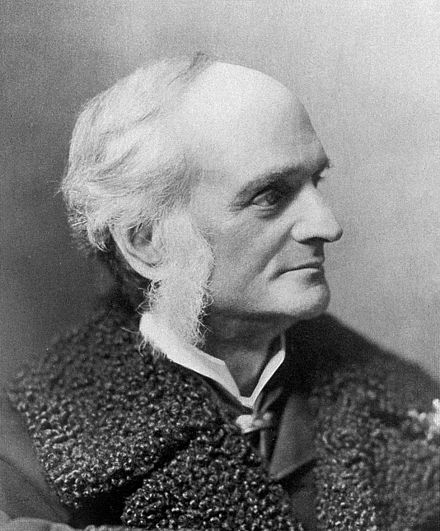

The clanger came in 1881 after it published a paper by Aberdeen surgeon Alexander Ogston on staphylococcus aureus, based on research funded by the BMA. Hart reportedly rejected further papers from Ogston with the words “Can anything good come from Aberdeen?”

Hart was a master of the put-down and would have been familiar with the journalistic maxim, never let the facts interfere with a good story.

There were no riots in Aberdeen. It had a reasonable claim to be the oldest medical school in the English-speaking world – against which the BMJ was just an impish upstart.

Ogston moved on, leaving experimental pathology to others, and taking up the regius chair of surgery in Aberdeen.

Both he and Hart were passionate campaigners for reforms in military medicine which prompted the creation of the Royal Army Medical Corps in 1898.

Hart also chaired the BMA Parliamentary Bills Committee which gave profile and a focus for his journalism, particularly attacking awful conditions in poor law hospitals and schools. He exposed the scandal of baby farming by placing a fake newspaper advert to flush out the greedy perpetrators who pocketed an average of £10 for every child handed over.

All of this earned him enemies and attempts to unseat him. Hart was particularly proud of his Jewish faith which enabled his critics to lace their hostility with the bile of anti-Semitism.

He could also skate on thin ice. One obituarist noted his 1859 monograph on diphtheria “bore little evidence that he had ever seen a single case of the disease.” A decade later he also mysteriously stood down for a few months after claims that he had pocketed payments to BMJ contributors.

He was at his polemical best with an 1880 pamphlet responding to claims by those opposed to vaccinations against smallpox: “…for gross misrepresentations, perversions, mis-quotations, and inaccuracies, and as a medley of utterly wrong and absurd ideas about pathology and physiology, I have never seen their equal.”

Hart was particularly scornful of doctors who sided with the anti-vaccinators. He articulated a vision of medicine based on sound principles and knowledge. Darker forces were at large: “…the whole herd of pill-vendors, bonesetters, and fraudulent quacks, who flourish now in thousands among us, whose vile practices do much to deteriorate the health of the people, and who annually rob them (especially the poorest) of a vast sum of money.”

The BMA also needed careful handling. A more accurate description then would have been the British Medical Men’s Association because they all had one small thing in common. And overwhelmingly, the membership opposed admission of women.

Hart thought differently. He worked closely with his wife Alicia who had studied medicine in Paris and later at the London School of Medicine for Women. Its dean, Elizabeth Garrett Anderson, came to Hart’s funeral, and praised him for his long-standing support behind the scenes.

Ogston was BMA president when it held its 1914 annual meeting in Aberdeen. Intriguingly, in his welcome speech to delegates, he made specific reference to a 1497 letter from Erasmus of Rotterdam to Aberdeen University’s first principal, Hector Boece. They were good friends from their studies in Paris. Erasmus started the letter with a flurry of insults all in jest – banter, in other words.

This might explain Hart’s waspish barb. More clues may lie in Ogston’s papers at Aberdeen University or the BMA library (which Hart founded in 1887).

Three days after the BMA meeting Britain was at war again. Ogston, by then Sir Alexander and aged 70, dusted off his army kit from campaigns in the Sudan and South Africa to join up with the RAMC.

Both Ogston and Hart remain largely forgotten now.

Hart’s legacy survived into the broadcast era. He would have approved of the first BBC broadcast by a Chief Medical Officer in 1941 when Sir William Jameson invoked Hart’s plain speaking to promote the UK’s first concerted vaccination campaign.

That was against diphtheria. It was also a good thing – Jameson was an Aberdeen graduate.

Sources

Update (February 2023) An excellent recent article on Ernest Hart by Kenneth Collins in the Journal of Medical Biography is available here: https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/full/10.1177/09677720221135122

Br Med J 1898;1:175- 86

In memoriam Ernest Hart, M.R.C.S., D.C.L (British Medical Journal, London) 1898

PWJ Bartrip’s DNB piece on Hart is particularly illuminating https://doi.org/10.1093/ref:odnb/12475

The truth about vaccination – a report on vaccination as a branch of preventive medicine by Ernest Hart (London: Smith, Elder & Co.)1895

The making of the body: a children’s book on anatomy and physiology for school and home use by Mrs. S.A. Barnett, London: Longmans, 1894

Br Med J 1914; 2. 2796, p 227

Categories: history on the web

Leave a comment